Blog – bees, beekeeping & other sticky subjects

If a product has a 96% efficacy rate in killing varroa, what does that really mean?

We’ve had a very good question from a Vita Bee Health product user.

“When you say there’s a 96.8% efficacy rate in killing varroa, what does that really mean? And what is the difference with the infestation rate?”

Paulo Mielgo, Vita Bee Health’s technical director gives the answer:

A treatment efficacy rate of 96.8% means that 96.8% of the mites that were in the colony during the treatment period were killed.

So, if there were 1,000 varroa mites in the colony before treatment, 968 would be found dead after treatment.

In contrast, the infestation rate is measured by an alcohol wash before and after treatment to count mite numbers. So, if there were 40,000 bees with an initial infestation rate of 2.5% (ie, 1,000 mites), a product with an efficacy rate of 96.8% would kill 968 mites of 1,000, leaving a post-treatment infestation rate of 0.08%.

Foulbrood diagnostic kits now available in the USA

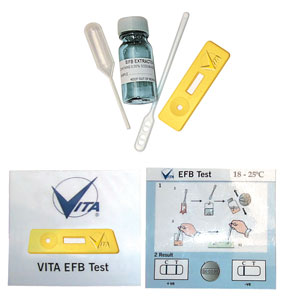

American beekeepers can now obtain Vita’s low-cost foulbrood diagnostic test kits – but not through the usual channels.

The kits can now be obtained by groups of beekeepers, bee inspectors, vets or university researchers for investigatory or research purposes. Just email for details.

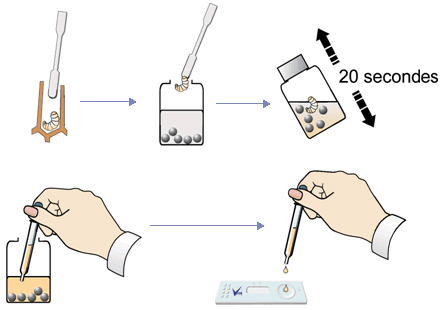

The American and European foulbrood (AFB and EFB) diagnostic kits, which work like pregnancy test kits, give results in seconds and so are very suitable for use in apiaries by beekeepers and bee inspectors. The two separate low-cost kits can give valuable early warnings of AFB and EFB and therefore help prevent the spread of disease.

The kits are already in use in 60 countries across the world by beekeepers and official bodies. Unfortunately registration costs in the USA would make the end cost of the devices expensive for American beekeepers, so they cannot be supplied through the usual channels.

However, Vita has discovered a perfectly legal and acceptable way to make the kits available to groups involved in beekeeping. All a group has to do is apply for a simple import licence – Vita can help groups do this and can then supply the kits direct to a group.

Vespa velutina has jumped the Atlantic

In August, Vita Bee Health’s social media account received a photo from Savannah in Georgia, USA, asking if the insect featured might be a yellow-legged hornet (aka Asian hornet or Vespa velutina) and what to do.

The insect was dead but it did indeed look like Vespa velutina, so we urged the sharp-eyed enquirer to report it immediately to the authorities.

At first, some local entomologists said it wasn’t the Asian giant hornet (Vespa mandarinia) — which was correct — but showed little further interest.

We urged him to keep reporting it and soon it was indeed agreed to be the insect that has been travelling rapidly though western Europe. But this was the first reported instance in the USA.

The alert went out and the nest was found.

Photo: Georgia Department of Agriculture

Sebastian visits Taiwan

Postponed for three years because the pandemic, Sebastian Owen of Vita Bee Health visits Taiwan to better understand beekeeping in the country. Here’s a short video of his trip. How many differences can you spot? Moving hives two at a time is a nice trick.

Do bees learn waggle dancing from other bees?

In a new video from Inside the Hive TV and sponsored by Vita Bee Health, Humberto Cristiani discovers new research about the honeybee waggle dance. In a cunning research design, it’s been discovered that bees do in fact learn how to dance accuately from other bees. He also discusses the effects that pesticides can have.